Edgar Allan Poe

Narrative of A. Gordon Pym Chapter 18

January 18.

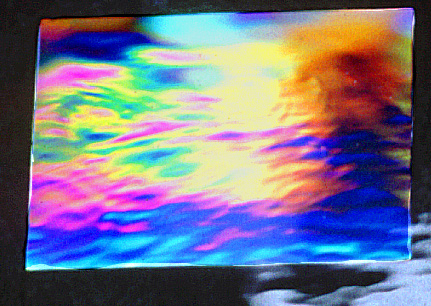

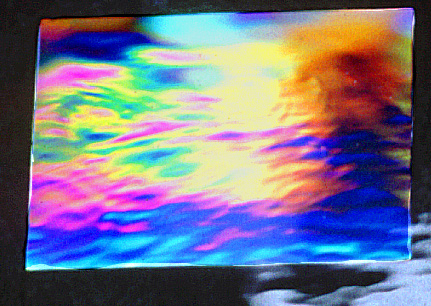

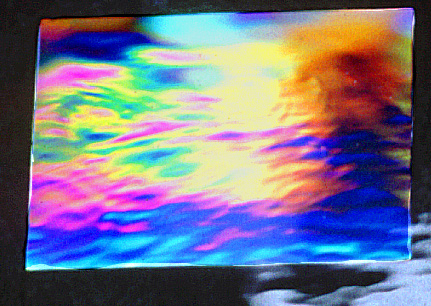

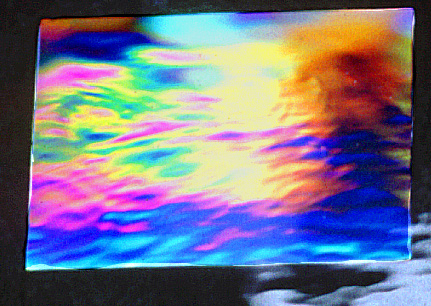

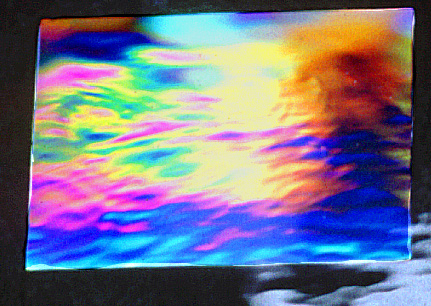

I am at a loss to give a distinct idea of the nature of

this liquid, and cannot do so without many words.

Although it flowed with rapidity in all declivities where

common water would do so, yet never,

except when falling in a cascade, had it the customary

appearance of limpidity.

It was, nevertheless, in point of fact,

as perfectly limpid as any limestone water in existence,

the difference being only in appearance.

At first sight, and especially in cases where little

declivity was found,

it bore ressemblance, as regards consistency,

to a thick infusion of gum arabic in common water.

But this was only the least remarkable of its extraordinary

qualities.

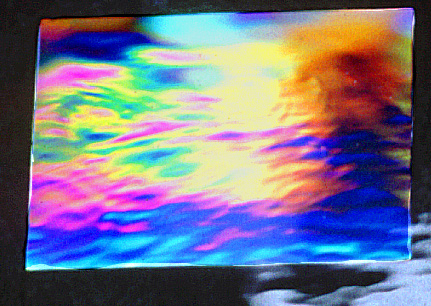

It was not colourless,

nor was it of any one uniform colour

- presenting to the eye, as it flowed, every possible

shade of purple;

like the hues of a changeable silk.

This variation in shade was produced in a manner

which excited as profound astonishment in the minds of

our party

as the mirror had

done in the case of Too-wit.

Upon collecting a basinful,

and allowing it to settle thoroughly,

we perceived that the whole mass of liquid was made up

of a number of distinct veins, each of a distinct hue;

that these veins did not commingle;

and that their cohesion was perfect in regard to their

own particles among themselves,

and imperfect in regard to neighbouring veins.

Upon passing the blade of a knife athwart the veins,

the water closed over it immediately, as with us,

and also, in withdrawing it, all traces of the passage

of the knife were instantly obliterated.

If, however, the blade was passed down accurately between

the two veins,

a perfect separation was effected, which the power of

cohesion did not immediately rectify.

The phenomena of this water formed the first definite

link

in that vast chain of apparent miracles

with which I was destined to be at length encircled.

E.A. Poe,

Aventures d'Arthur Gordon Pym.

XVIII.

Je ne sais vraiment comment m'y prendre

pour donner une idée nette de la nature de ce

liquide,

& je ne puis le faire sans employer beaucoup de mots.

Cette eau n'avait jamais

l'apparence de la limpidité.

A première vue, elle ressemblait un peu, quant

à la consistance,

à une épaisse dissolution de gomme arabique

dans de l'eau commune.

Elle n'était pas incolore;

elle n'était pas non plus d'une couleur

uniforme quelconque,

& tout en coulant elle offrait à l'oeil

toutes les variétés possibles de la pourpre,

comme des chatoiements & des reflets

de soie changeante.

Pour dire la vérité,

cette variation dans la nuance s'effectuait d'une manière

qui produisit dans nos esprits un étonnement aussi

profond

que les miroirs

avaient fait sur l'esprit de Too-wit.

En puisant de cette eau plein un bassin

quelconque,

& en la laissant se rasseoir & prendre son niveau,

nous remarquions que toute la masse du liquide

était faite d'un certain nombre de veines distinctes,

chacune d'une couleur particulière,

& que ces veines ne se mêlaient pas.